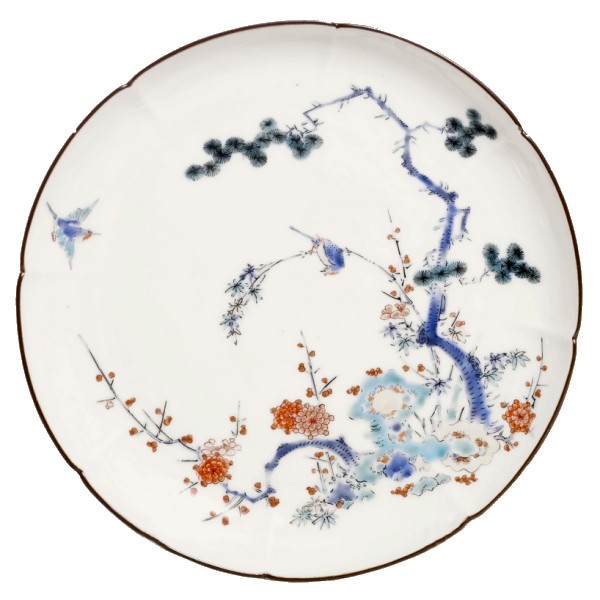

A Japanese Kakiemon saucer dish, late 17th century, c. 1670-1690.

Asymmetric composition as opposed to symmetric composition, is particularly seen in older Chinese silk paintings and for example Japanese Kakiemon decorations, aligns with the principles of asymmetrical balance and negative space.

Asymmetrical balance differs from symmetrical balance by not mirroring elements across a central axis; instead, elements are placed unevenly but in a way that still achieves a visual balance. This kind of composition often leads to more dynamic and interesting visuals compared to symmetrically arranged designs.

This technique is central to many Asian art traditions. In Japanese art, this style can also be related to the aesthetic principle of "Ma" (間), which emphasizes the importance of negative space in composition. "Ma" refers to the interval or void between things, and is considered an integral part of the artwork, contributing to the overall balance and interpretation.

Symmetry in Asian art is seen as evoking a balance of elements in which there is no possibility of flow or movement of ch'i, 気 (ki in Japanese).

The use of negative space is also crucial in this style. Negative space (the area around and between the subjects of an image) plays as much a role in the composition as the actual objects or subjects. This space is not merely empty but is an active part of the artistic composition, providing "breathing room" for the eye and creating the visual balance that makes the art piece intriguing and aesthetically pleasing.

In Japanese art, this concept can be closely linked to wabi-sabi, an aesthetic philosophy that appreciates the beauty in imperfection and transience, often embodying simplicity and understated elegance.

Asymmetry in East Asian art, exemplified by Chinese landscape paintings and Japanese gardens, is deeply intertwined with foundational Chinese and Japanese philosophical principles. This artistic preference for asymmetry reflects the profound influence of concepts such as ch’i (or ki in Japanese), yin and yang, and the dynamic flux between these elements. Ch’i represents the vital life force or energy that pervades the universe, believed to be generated through the interplay of yin (the receptive, feminine aspect) and yang (the active, masculine aspect). These philosophical notions emphasize that true harmony arises not from static balance but from continuous transformation and movement—principles inherently opposed to the rigidity of symmetry.

In Chinese and Japanese thought, each element contains the seed of its opposite, meaning that each is always evolving into the other. This continuous flow and transformation are crucial for the sustenance of life and energy, which symmetrical designs might impede, leading to stagnation and a lack of vitality. Therefore, asymmetry in art is not a mere aesthetic choice but a reflection of a deeper metaphysical reality that aligns with natural principles as observed in the world around us.

Thus, the asymmetrical compositions in Chinese and Japanese art are not only a stylistic choice but also a philosophical statement, embodying the fundamental beliefs about nature, energy, and life's ever-changing essence. They invite the viewer to participate in a dialogue with the artwork, fostering a holistic experience where the viewer and the viewed are no longer distinct but part of a continuous, harmonious whole.

A