Went back to the Longzhu (dragon's pearl) pavilion on Zhushan where many of the reconstructed objects apparently were stored. It felt unlikely that all of these rare excavated objects would be stored there, but as far as I could see all pieces that we are shown are brought out from a variety of cabinets in and around where we sit. During this visit I was welcome to take photographs. That was good since only the camera equipment I somewhat optimistically had brought this time around to Jingdezhen easily weighed more than the free hand luggage allowance on the flights.

I had probably got it through the airline check-in's thanks to some uncertainty regarding what constitutes a 'camera', since my heavy black aluminum box was neatly labeled Hasselblad and a number '2' subtly hinting that there is probably a number '1' around somewhere too, and that we were getting off easy if we only had to deal with one of them.

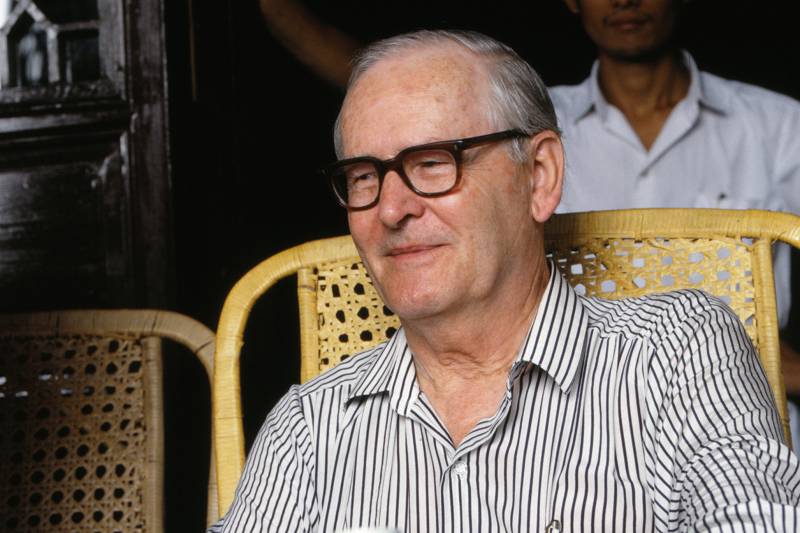

Professor Bo Gyllensvärd, Studying Imperial Kiln excavated porcelain, September 1992

Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 1992.

We were seated in a beautiful, brightly lit salon on the south side of the pavilion. A row of louvered doors was opened to the outside. Suddenly we had a fascinating view over the old imperial porcelain factory area. I felt very privileged. The sky over the old Imperial factory ground just outside, was the same as from time immemorable, the same birds chirping as were the warm wind sweeping in through the windows.

Perfectly unhurried I could photograph object after object from the Yongle (1403-25) and Xuande (1426-35) periods at the rate they were brought out for us to see.

Pear shaped vase. Underglaze blue and white decoration of one large and four small five-clawed dragons. Thin walls. Ring foot and base fully glazed. Late Yongle period, unearthed from late Yongle stratum in 1984. Height 26.9 cm. No mark. By the end of the Yongle period it appears as if underglaze blue and white pieces are made for the personal use of the Emperor and not only for gifts or export.

Some observations: One characteristic was that all surfaces were very much worked. A smooth bottom surface inside of the foot ring of a common large dish from Xuande gave the impression of having been processed endlessly with a small spatula to become this smooth. The large dishes bottom rings were not cut but just fairly rounded. On the ground just outside the pavilion where we sat, I found a part of a large firing patty that exactly matched the underside of a dish from Xuande, with a small trace of blue glaze stuck to it, similar to the glaze on some of the pieces we were looking at inside.

Fig. 14. Profile of fairly rounded, not cut, foot rim from Xuande (1426-35)

Monk's cap jug. Four character Xuande mark on the base, and of the period. Underglaze blue and white decoration of double horned five clawed dragons and Tibetan characters. At 23.4 cm this jug is 4 cm higher than the white incised decorated early Yongle jugs from stratum five in Zhushan road.

Basin with a Longquan-type celadon glaze. Diameter of mouth 27.8 cm. Low foot and gritty base that has turned brownish red in places.

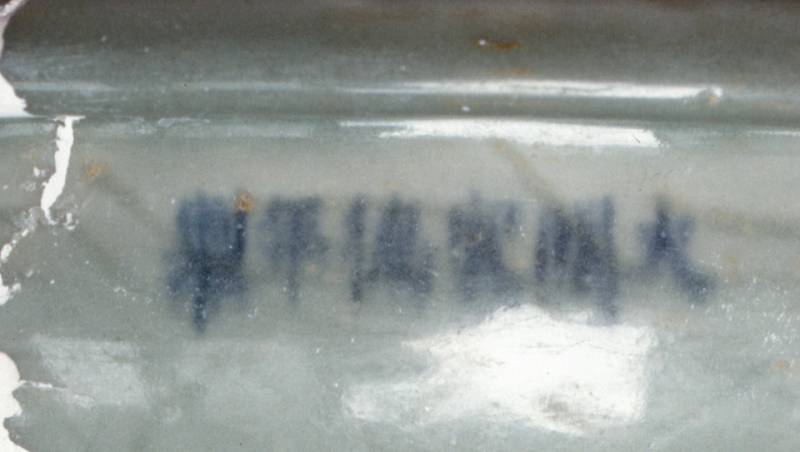

Six character Xuande mark written horizontally under the outward curled rim.

Six character Xuande mark

Fig 13. I carefully studied the large dish with white reserved decoration on a blue background from the Chenghua period (1465-87).

There were no tool marks left at all that cold give a clue on how the reserves had been created. The blue were perfectly even and so was the white body. One could guess that a wet paper could have been applied to the surface that were to be kept white, or maybe the decoration that was supposed to come out white could have been made raised and then removed? Maybe several different techniques were used on the same subject.