Basically, from here you are looking straight up to it. If you look slightly to the right, its a mountain missing there. It's no small quantities of 'kaolin' we are talking about being quarried from here over the centuries.

Fig 5. The Bridge over the Dong River led through the small village of Dong Bu and up into the Gaoling mountain - the High Ridge - which was visible in the distance shrouded in mist.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

This day we had made a serious attempt to try to limit the number of participants in our excursions. I had tried to explain that to us, it was perfectly enough if one or maybe two persons joined us, maybe our friend Zhen and the interpreter would be enough. We genuinely felt bad about imposing so many favors from Dr.s Liu's office staff, drawing such a large group as the usual crowd that hung around with us from their work.

At this the entire group of archaeologists and whatnot, that had happily followed us in our trail since we arrived, looked so disappointed that we realized our cultural faux pa and declared, that we of course would be extremely happy should they want to join in.

This said and done, we rented a small tourist bus that could accommodate all of us and off we went.

There were a variety of ceramic workshops along the road. In several places we saw large woodpiles and in one place a limestone quarry. We drove along the river Dong that in old times had been used to ferry the 'gaoling' china clay down to Jingdezhen. It was now very little water in it which may have been due to the season. During the morning we saw a few smaller dams that locally raised the water level slightly.

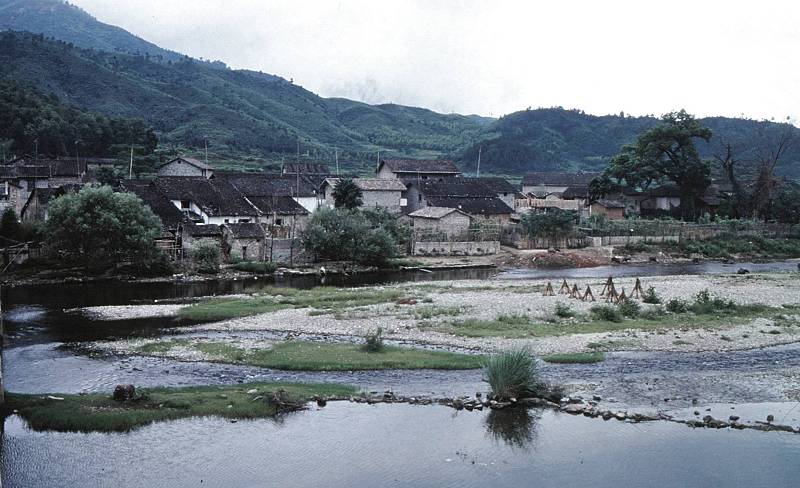

Dongbu village, downstreams, Gaoling 'High Ridge' in the distance

Fig 6. Dong Bu village.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

Dong Bu village.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

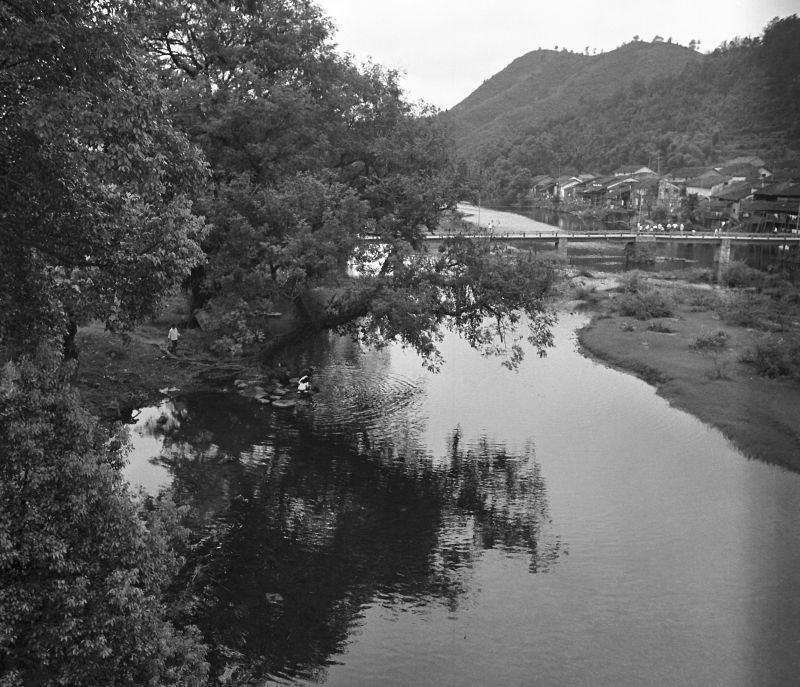

Fig 7. Dong Bu village low bridge. View north from the high bridge. At the river bank is a small paved quay or revetment.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

Gaoling is located about 50 km north of Jingdezhen. The first stop was a village called Dong Bu. We took off from the main road, went down to the right, through the village, over a bridge and then miles and miles up into the Gaoling high ridge mountain along a little steep, curvy, hilly and narrow gravel road with no railings.

Covered bridge with 6-7 man-high stone tablets

We stopped at a covered bridge rather like a Swedish water mill. Under the roof of this building were 6-7 man-high stone tablets. It was dated donor plaques with the names of those who had contributed money to the bridge. The oldest board appeared to be from Yuan. There were also tablets from the Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-1735) and the youngest we saw from the Jiajing (1796-1820) period during the Qing.

These late dates was a bit odd to find since during Wanli (1573-1620) they had ended the large-scale mining according to the foliang County History due to that the clay had run out. The clay mining had assumed such proportions that the fields below the mountain was destroyed by the gravel rinsed out of the clay. The farmers complaints had caused the districts mandarin to announce that "the clay was all out".

At the covered bridge was a dilapidated water hammer facility. When I asked what this had been used for, they replied that it was just an example and that the porcelain stone was never crushed here.

That might certainly be true, but the old silk paintings that describe porcelain manufacture sometimes show water hammers associated with what appears to be Gaoling quarrying. I cannot thus exclude that they at some time used water hammers to crush the gritty Gaoling raw material.

Old clay mine tunnel

Nearby there was a narrow passage into the hillside. This was an old mine tunnel, they said. I lay down on the ground and crawled in. A few meters down the hole got somewhat wider so that I could raise my head and look downwards, and saw that the hole turned into a meandering tunnel. I shouted at Jarl who also crawled in. Using his cigarette lighter as a torch we investigated the roof which to both of us appeared to be composed of mortared stones. Thus all pointed at that this in the same way as with the water hammer was just for the tourists.

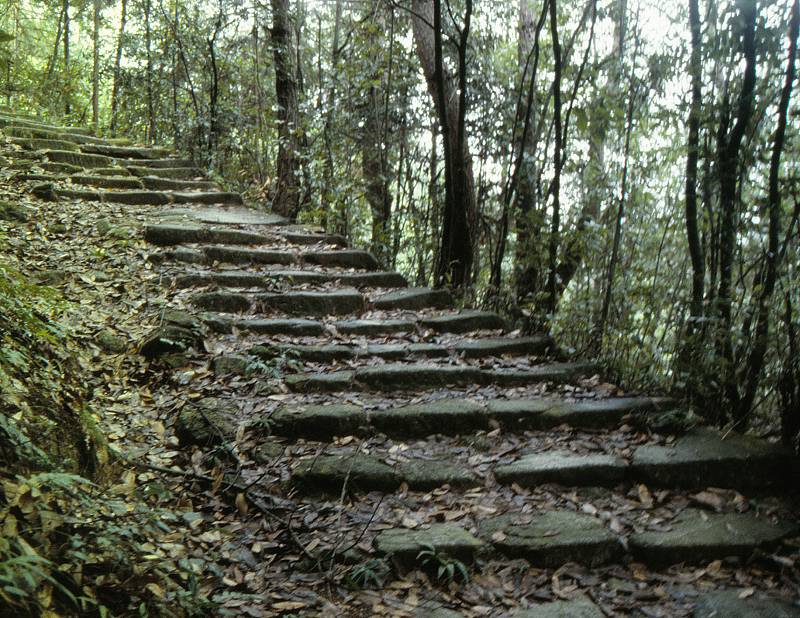

A staircase in the rocks led upward. We started walking up along this and followed it for several hours. Our bus effortless caught up with us later after one of the paths up the mountain, so what we had followed must have been the expected route.

From what I could understand the entire mountain actually consists more or less of "Gaoling clay", however of different purity. The raw material appeared to be a white, granular and porous mineral, perhaps weathered granite. Between the solid particles was a white powder that was the clay itself. If this material was crushed the clay could be rinsed out. The purity could differ; at the best places they had been able to find completely pure clay, told our companions. If we assume that what happened during the Wanli was that the premium clay quarries was not enough, one can indeed imagine that mining of this low-grade clay , which must be washed and silted, certainly would cause lots of waste gravel.

All that we could observe suggested that the clay actually had been mined in huge day quarries.

We looked everywhere for traces of mines, paths, mine shafts or other facilities. What I think I can confirm are:

Mineral samples place.

Fig 8. View of Dong Bu from the Gaoling ridge. From Gaoling I could see along the gully down to the village where the farmers during the Ming must have complained that the gravel from clay quarrying was destroying their fields.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

Open ground up at the Gaoling. The white patch shows this grainy material that obviously was the China clay itself.

The bus effortlessly caught up with us much later, up at the hill.

From there we went on to Nanpo.

Our accompanying archaeologists said about here, that during the Qing Dynasty, it was found a better place for "Gaoling" clay, in Qimen, that was closer to Jingdezhen and where the clay was easier to mine.

We went back to our bus and continued to the district capital that was Nanbo. This is also an old kiln area. Our hosts invited us to a lunch at what appeared to be the local the local military outpost. We showed our colors at an improvised table tennis tournament, since the table was there and the food was still in the process of being made.

The buffet turned out to be very nice and in particular I found the omelet as one of the best I had ever had, so much so that I asked how it was made. Our host gave me a completely blank stare and explained that, you take a few eggs and then you stir with the chopsticks. Upon leaving, I eventually noticed that the secret was rather their supply of completely free roaming hens and their healthy diet of local seeds and bugs that was the entire explanations to the good eggs.

From here we were to continue to an important kiln area further north called Yaoli. The road went through a lush, beautiful region. All the time we followed a little river channel that more and more turned into a small stream. Once we arrived at Yaoli, we just continued straight through. Perhaps our hosts thought that we literally just wanted to 'see' Yaoli and that we could do from the bus window. It is hard to tell if there were other reasons for not wanting us to see Yaoli, but this we could just speculate about.

After a while we came to the next kiln area called Raonan. Here we managed to stop the bus and to go out also got to see a beautifully located water hammer for crushing china stone. The porcelain stone mining for this hammer took place just north of Raonan and the clay silting process was done here quite seriously in this traditional water-powered facility.

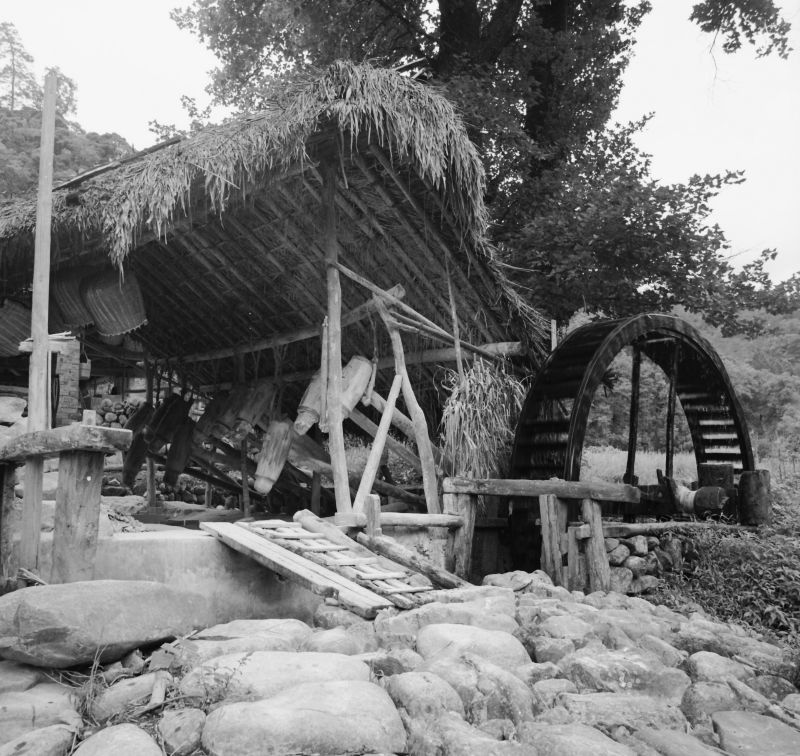

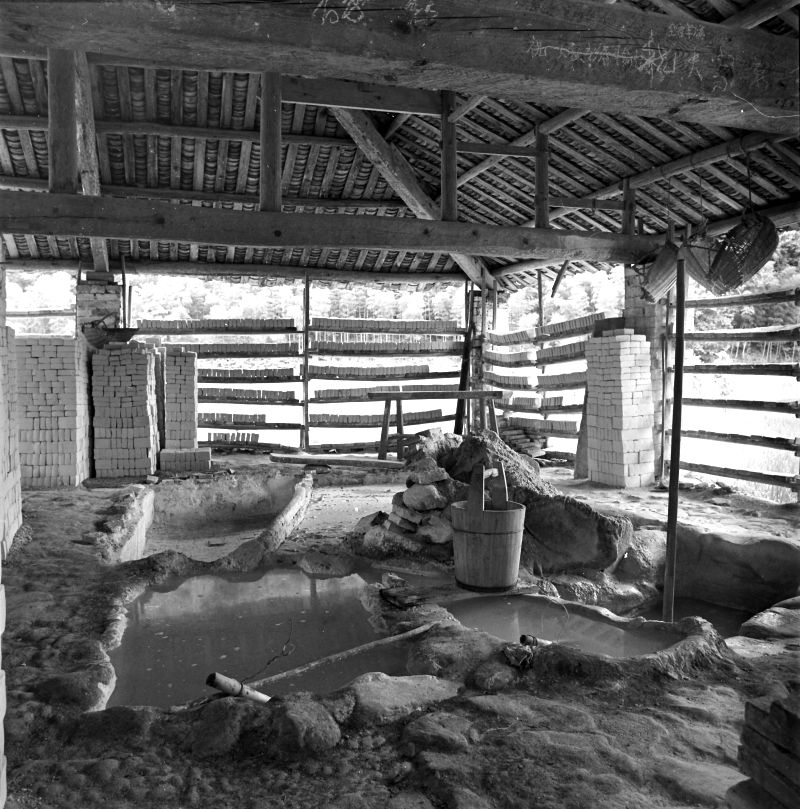

Fig 9. At Raonan, north of Gaoling and just north of Yaoli was this little beautiful water powered rock crushing facility in full use.

Since the stream was now a mere trickle, several of the pounding hammers were disengaged. Here porcelain clay was manufactured in the traditional way. One of these white "Bai tun tzi" bricks was brought back home.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

Here I asked if I could actually have one of these clay bricks as a sample to bring back home. Yes, please help yourself they said, I think. My question was put in Swedish to which the answer was given in Chinese, which I understand as much of as they did Swedish. After much lugging this now finds itself at home in Sweden.

Fig 10. Raonan water hammer slush ponds.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

Fig 11. Raonan water hammer white bricks drying.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, September 9, 1992.

After a short walk downstream along a small rural dirt road between some fields, we arrived at Raonan's old kiln area. The waste pile as we could see was about 50x200 meters and maybe 30 feet high at its highest point. Here was found a small dragon kiln. The production was believed to have ceased during the late Ming (1480).

The oldest qingbai fragment we saw seemed to be a shufu type ware from Yuan, but what may lie at the bottom of the large shard mound one can only guess. The majority of shards were early blue and white porcelain simply painted with early Ming type of spirals and in one case a seashell. The body was grayish and had fired red. The foot rim was rounded. We found virtually exclusively only bowls that had been fired standing inside one another on a circular area from which the glaze had been scraped off.

Loose shard samples found on the ground at Raonan. The stepped saggar fragment actually point at fousaho upside down firing, and that dates this kiln as far back as Song. It is indistinguishable from the same type found in Hutian.

There were other furnaces in the area from the Five Dynasties (907-960) we were told. It is worth mentioning that the Chinese dates their porcelain both after style and historical documents, so their conclusions might differ from ours due to this.

One may have produced porcelain for both the Emperor and from the people's kilns (minyao). Especially is this likely with regard to so-called "provincial Ming" which may well have been manufactured by imperial command to be used as gifts. Especially worth considering is this with regard to the well-known order of 443 500 porcelain items from Raozhou in the year 1433. In 1433 it is two years left of the Xuande period. After this it becomes the Zhengtong period and the uncertainties of the interregnum period begins.

Archaeological studies also show how, during the Interregnum, when the imperial manufacturing lies down there is a big boom in Hutian especially regarding the production of stem cups. There is thus a possibility that large amounts of the "early provincial goods" we find in the Philippines and everywhere else in the Southeast Asian islands are remnants of this gigantic order, to which the entire province must have been forced to participate to deliver. About 1433-35 cobalt decoration become the norm on Chinese porcelain.

All around Jingdezhen is a variety of major known kiln sites with large shard mounds. The impression one gets is that the production has been very intense over a period and that they then dumped one last load of waste over the edge and them went home. In theory, there is a possibility that these kiln sites was set up especially to for a short period produce large amounts of fairly similar pieces, such as bowls of only a few sizes, or at other places only stem cups with medium-high foot ring, etc.

It is currently impossible for me to come to any conclusions on this but hope that further studies, or when I can get hold on some literature, will clear this out. For the moment I will just take down the questions.