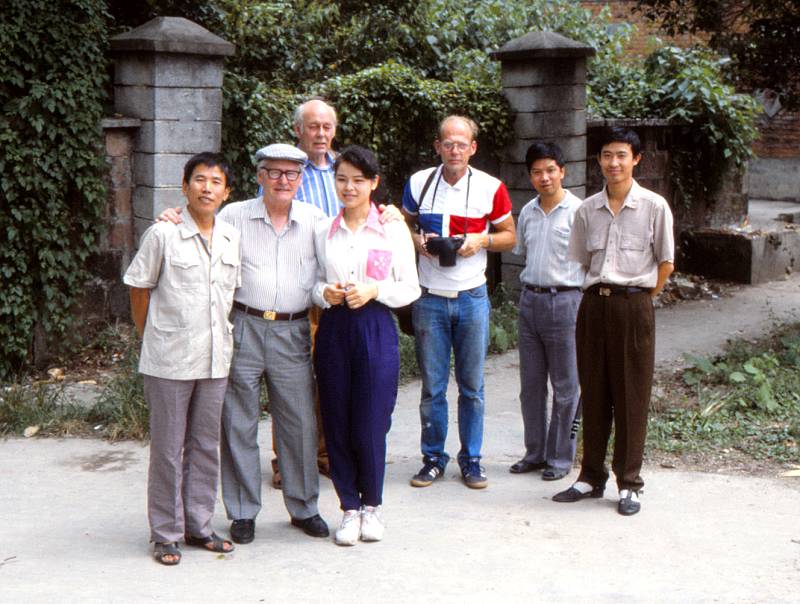

Our group outside the Hutian Kiln Site Museum, near the Fuluyao kiln. Our group surrounded by our friends and hosts from Jingdezhen Archaeological Institution. Us, from left to right Professor Bo Gyllensvärd; In striped shirt, Erik Engel and next to him, Jarl Vansvik, both Curators at the Ulricehamn East Asian Museum, with the Carl Kempe collection; In the foreground, our interpreter, borrowed from the Hotel; Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 1992.

The Hutian visit began with a tour of the Hutian Kiln Site Museum. This was established in 1979 for the protection of the site. This was unfortunately only after the Cultural Revolution during which they had flattened a great part of this area to build houses. We presented the director of the museum with a lidded sugar bowl from The Rörstrand Ostindia service as a gift. They were really impressed with the technical quality and the fit of the lid. We asked if he could help with identification of Bo's shards from Fostat.

They could positively identify all as Yuan-Ming dynasty minyao, and almost all of them from Hutian, although this area in the local dialect here is actually pronounced 'Futien'. This aroused within parentheses many questions on possible misunderstandings in the history of porcelain research.

Fig 2. Map of Hutian. Copied from a landscape model in the Hutian Kiln Site Museum September 10, 1992.

Names and dates becomes easier to read if we remember that Bei=North and Nan=South.

A walk around in these since last year beyond recognition freshened up blocks provided a good view over the various old kiln's locations.

During the 1970s, Dr Liu Xinyuan and Bai Kun of the Jingdezhen City Museum of Porcelain History, made a number of salvage excavations of some important places. They registered the gourd-shaped and the hoof-shaped kilns of the Ming Dynasty, and in 1979 had walls built around the Liujiawu (Five Dynasties), Wangshiwu, Pipashan, Huluyao and Wuyuling (Song/dragon) kilns.

The finds here dates from the Five Dynasties, Northern Song, Southern Song, Yuan and the Ming Dynasties i.e. from 10th to 17th centuries.

Hutian Kiln Site Museum shard storage jealously protected from our inquisitive eyes.

What is probably the most obvious are the blue and white shards that is not much talked about.

The porcelain industry at Hutian started in the Five Dynasties period with the earliest kilns located in the center of the area. It grew so much that in the middle of the Northern Song it occupied the whole northern side of the Nan Mountains. At the end of the Northern Song, through the Southern Song to the Yuan dynasty, the industry covered the banks at both sides of the Nan River. During the Ming Dynasty, the industry had moved to only the banks of the Nan River.

Only a few actual kilns have been found which might be caused by the remnants is buried under the mounds of kiln waste, or of course, that they have just not been found.

The hoof-shaped kiln was popular in the Five Dynasties period, and the Ming Dynasty, leaving the Song and Yuan dynasties in the middle, where it seems like dragon kilns might have been preferred. The inside area of a hoof-shaped kiln is roughly 10 sqm.

A dragon kiln have a much larger throughput and might have been preferred because of that. Its just a tunnel, uphill, that could be made as long as you like and you fire it with whatever at hand. They are still being used in Shiwan, near Guangzhou, and are fiercely efficient.

In A. D. Brankstone's book The Wares of the Early Ming Dynasty (1937), he indicates that the porcelain market is south of Jingdezhen, on the Jingdezhen side of the Nan river, where it joins the Chang jiang. It is a very logic location and might very well predate Ming.

Hutian kiln area shard samples found scattered on the ground. Where we had expected to find qingbai only,

it was surprisingly easy to find black glazed wares. Both temmuko style bowls and stemcups.

Notes

Rough rim Porcelain

Firing capsules (saggar) halves.

Yuan Dynasty used different Gaoling-clay.

Black colored Yuan.

Min yao = made by / for the people

Guan yao = made by / for official.

Flower shape.

Qi Li Chin = black wars.

Fig 3. Broken part of Shufu stemcup drawn as found in a shard storage in the Hutian Museum, September 10, 1992.

Kilns mounds are scattered all over the Hutian area

In Hutian during the Five Dynasties no saggars was used. Porcelain, mostly low shapes in green and white colors, was fired, separated by 9-16 small spurs or wads of clay that needed to be whacked or rubbed away from the surfaces.

From early on in the history ceramic objects have been fired inside a protective outer jar, made of rough clay, called saggar.

Fig 4. Street view from the city of Jingdezhen, September 1992.

A cartload of modern saggars for flatware. Basically one of these will only hold one plate. According to what I understood, modern saggars like this could be placed in column as high as thirty on top of each other in the kiln. Still, that only makes thirty plates per one column. On this load there seems to be about one hundred saggars, enough for three columns, or 100 plates.

Photo © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Jingdezhen, China, September 1992.

Their function was to protect the fragile and sensitive unfired porcelain from whirling sand, flames and ashes during the firing, to ensure an even temperature and make it possible to economize with the kiln space by making stacking possible of glazed ceramics. By stacking the saggars on top of each other in high piles there was created space in the kilns for a large number of pieces. In general the quality of the wares stood in reverse relation to how many pieces that was fired at the same time. Unglazed pottery, was otherwise just stacked on top of each other quite unceremoniously.

The saggars are in general expected to have a certain life span and that they could be reused for a certain number of times. Naturally the risk for disasters increased with the number of pieces fired at the same time. If just one saggar collapsed, whole stacks could naturally collapse, sometimes entire kiln contents was lost.

The two main difference was if the pieces was fired upright standing, resting on their footrim - or upside down (fushao), resting on its mouth rim. Firing bowls and dishes upside down resting on their mouth rim made it possible to fire a large number of pieces at the same time but resulted in an unpleasant unglazed rim.

The fusaho was perfected at the Ding kilns in Northern China during the Northern Song dynasty (1086-1127). It appears likely that some of the Ding potters that worked for the Song dynasty court followed the court when they were forced to relocate their capital to Hangzhou around 1127. Somehow this technique eventually found its way to Jingdezhen.

The fushao firing gave several benefits. One was that the kiln managers could save on fuel by firing a greater number of pots at one time. Speed might be one consideration since more pieces could be made at the same time. Then you had the issue of shape. Anything that melts will eventually go out of shape. This could be dealt with by resting the objects upside down on their rims. In the South of China this issue could be addressed by mixing in an un-meltable ingridience (kaolin or china clay) to the porcelain body and thus create a special paste that had an inner structure by itself - which is the very secret of porcelain. Kaolin was however in short supply and the use of this special ingredient created a whole number of other aspects to consider.

Usually a saggar is a round straight sided vessel with a flat bottom that seems to have been covered with fine grit or kaolin powder. Stacked on top of each other they would form columns that could go from floor to roof inside the kilns. Empty saggars - even whole rows of column of empty saggars - could be used as protection and supports depending on what was supposed to be fired.

Most of the time special setters and supports was used inside the saggars to keep the porcelain pieces from not sticking together or to the bottom or walls of the saggars. The porcelain cold be set on a cake of porcelain clay, sometimes dusted with rise husk ash. Sometimes a ring or a wad of clay, a flat bun of unglazed porcelain clay or, and intricate stepped bowls or rings was used. Sometimes grains of sand was used and sometimes the glaze was just wiped off of a part of the inside of one bowl to make it possible to rest one bowl directly inside another.

The kind of saggars and firing techniques used, has varied over time and geographic locations. A keen understanding of these various methods is a most valuable tool for dating ceramics and what very much what I hoped to get a better understanding of in Hutian.

Step setter appears to have been manufactured individually for the bowls that would be fired and to have been used only once. Generally shaped as a bowl with curved sides they had on their insides cut 6-7 steps of different diameter, that must have been made to fit one bowl each. These setters have very thin walls and each "step " is just a few millimeters wide. Some of these setters also seem to have a feet that may have been the cover a for one more, to fit under the first one as a lid. This type is encountered during the Southern Song (Nan Song) from 1127 to 1279 together with ring saggars.

Fig 4. Section of a an inside stepped setter. Most likely used inside a larger saggar to facilitate firing of a number of bowls and dishes at the same time. Most likely this was made to exact specification, fired at the same time as the vessels, and made of a very similar clay as the porcelain. Southern Song (Nan Song) in 1127-1279. Observed and drawn in Hutian, September 1992.

While ring setters would only accommodate bowls or dishes of one diameter, this kind of setter would accommodate a whole set of bowls or dishes with various diameters. The dish on this picture is only 4 inches / 10 cm in diameter and fits the lowest step in this setter perfectly. The setter fragment from Hutian, Jingdezhen, dish from private collection. Photo Jan-Erik Nilsson, Sweden 2014

Fig. 5. Both unfired raw clay and fired ring saggars was built in the same manner. The unfired was disposable and was built up ring by ring of wet clay with the bowls inside. It was then sealed with an outer layer of clay, and had to be broken to get the bowls out when they were done. A risky procedure to say the least. The second consisted of loose rings that could be reused. Available at the Hutian museum and the Jade Court, Jingdezhen.

One kind of setters for pieces of uniform size could be made out of rings of fired or unfired rings. These rings was piled one on top of another each other making up a stack of rings each holding a bowl or dish, of the same diameter as the one below. Finally the whole cylinder would be clad with an extra layer of clay.

For larger bowls this would be a very rational method. The above step setter would be used to accommodate smaller sized objects.

Stepped saggar for fushao firing

Stack of misfired qingbai dishes, fired fusaho - upside down - resting on their rims.

One kind of saggars we did not find here was a kind that was all over the place upstream's and on the other side of the Nanhe river, not too far away from here, at the Huangnitou and Baihuwan kiln areas.

Quite likely this kind of saggars might have been used here too but I just didn't see any. However, that is another daring way of economizing with kiln space. The piece that is to be fired was placed on a small lump of clay inside the saggar, that is made so that it will utilize the inside of the bowl below, to make space for the foot of the one on top.

Then these recessed base saggars could be stacked on top of each other as high as you dared.

Recessed base saggar with support wad. Archive picture, Photo Jan-Erik Nilsson, 2014

Inside a recessed base saggar. Archive picture, Photo Jan-Erik Nilsson, 2014