Some observations: During Chenghua (1465-87) suddenly a wealth of shapes and decoration appears. They both create new and imitate the old. I would actually say that the quality is not notable improved during the Chenghua period but maybe the quality becomes more even. The objects become thinner, lighter and weaker. The new shapes give a softer impression than the older ones, while the decorations in general are dark and hard. From what I've seen Chenghua-marked objects with pale light under glaze blue decoration not Chenghua but Yongzheng (1723-1735). Genuine Chenghua is playful. The thought that arises is that it may just be the imitations that in reality are as great as they say that the originals were.

Fig. 15. Box with lid and dividers. High foot rim. Bottom thinner than the outer wall. Straight cut foot rim. The blue color is like a cross between Qianlong and Yongcheng. Tougher shape, the body more even than in Yongcheng. Chenghua (1465-87).

Chenghua box with compartments. I think the box drawn above is the one to the left on this picture.

Photo by Jarl Vansvik, Jingdezhen 1992.

Dark clear color that goes from light to dark in the same brush stroke faster than on other wares I have seen.

Fig. 16. Dish with decoration of qilins. The bottom surface is incredibly well smoothed and shows no traces of hand or tool. Chenghua (1465-87).

Diameter about 30 cm. Interior decoration: 2 Qilins in the mirror, 2 lines on the rim and 2 around the mirror. Exterior decoration: On the outside 6 qilins with dragon's head, scaly body, bushy tails and hooves, 2 +2 +2 rings. Bottom burnt red and dotted as on older wares. The foot rim itself is more narrow. The actual bottom surface is incredibly well smoothed and shows no traces of hand or tool.

Fig. 17. Censer with oddly curved ear-loops. Chenghua (1465-87).

Censers, Chenghua (1465-87) mark and period.

Photo by Jarl Vansvik, Jingdezhen 1992.

We saw two similar censers with enamel decoration in yellow, dark grass green and red where the yellow and green had been fired simultaneously. Red under the feet. The red is by mistake covering the yellow edge of one of them.

On the censers above the nianhao is unevenly drawn. Marks are on the whole placed a little bit anyhow. If we count the characters 1-6 with Da as 1, one part of 2 Ming drawn as an "S". The 5 Nian character also clearly sits higher than the no. 2 Ming. The whole group is slightly diagonally organized. The square double frames that surround one of the marks are uneven and sloppily painted.

Fig. 18. Dish with the three iron red dragons on a white base. Chenghua (1465-87).

Fig. 19. Dish with the three friends. Chenghua (1465-87).

The weakness of the decoration is similar to blue and white Yongcheng. The general character of the dish and the nature of the blue is similar to that of Qianlong. Cut straight foot rim with knife marks.

Fig. 20. Foot rim on Doucai-dish with Qilin. Chenghua (1465-87).

Some observations: The yellow enamel is saturated and dark. The green goes towards grass green blue. The decoration in the mirror is a horn adorned qilin, without scales, which is relaxing amongst the clouds. The animal is drawn with personality and its look is worried. Square seal mark. No foot rim.

Some observations: On pieces from Chenghua, the body is usually thinner inside the foot rim than outside. A drooping bottom is a serious defect, and a way to overcome this may be thinner body. Another method is higher kaolin content or a support.

Fig. 21. Doucai bowl of high type. Chenghua (1465-87)

A few observations: We got to see quite a number of high bowls with the typical medallion decoration. Also in the square marks on these, the characters were placed somewhat diagonally. The foot rim is cut, rounded and polished in such a way that the knife marks are visible. A bowl was decorated with fruit baskets in the medallions surrounded by symmetrical cloud patterns. Doucai was here translated with "opposite painting" meaning on "both sides of the glaze". On all high bowls of this type a delimiting ring was missing on the middle level. All brims of the present sample is slightly flared. The bottom is in all cases thinner than the sides. The walls have potting marks or finger sized surface irregularities. The bottom is in all the examples drooping downwards.

Fig. 22. Doucai bowl of high type. Copy of Yongle. Chenghua (1465-87)

One bowl differed from the others. It was a Yongle period copy (1403-25) made during the Chenghua period (1465-87). Brim was not flared.

Finally two copies made during the Chenghua (1465-87) were presented.

Low bowl, Chenghua copy of Xuande (1426-35)

The Xuande copy has 2 +2 +2 rings on the outside. Sanskrit characters on the brim. On the inside 2 +2 +2 rings and decoration of three aquatic plants.

Low bowl, Chenghua copy of Zhengtong (1436-49)

The Zhengtong copy also has 2 +2 +2 rings and decoration of two ducks and two aquatic plants.

Fig. 23. Large platter, Copy of Xuande (1426-35). Chenghua (1465-87).

Large platter, Chenghua copy of Xuande (1426-35)

Could very well be the only one there is. See Fig. 23 above.

Bowl, Chenghua copy of Xuande (1426-35)

Decoration inside of two playing lion. The Imperial mark on the base very bad.

The afternoon was spent with the archaeologists that especially showed us doucai bowls. During Chenghua there was a tendency to prefer few boundary lines around the decoration. This was also demonstrated by when they during the Chenghua copied an older period, the tended to exaggerate the typical and simply add more rings than even the original had (cf. Liu Fig. 89). A copyist would strive to exaggerate the typical from the copied period and many boundary lines were a legacy of the Yuan (1279-1368) that must have felt "ancient" at the time of the Chenghua period.

Met during the evening, in the park below the hotel, with a porcelain dealer thanks through the mediation of the interpreter Xinjie that we had borrowed from the hotel. The tropical air was warm and humid. The street lights blinked and died. Bright in the middle of the night anyway, thanks to the full moon glistening in the lotus pond. This same moon had barely a hundred years earlier shone over the Eight Friends of Zhushan when they met around here to talk modern and innovative porcelain, very likely over a glass of wine.

Later in the evening we were visited by our daytime interpreter together with a hopeful companion, manager of Special Ceramics something. They showed us a Wanli-marked black and red-decorated pot with perfect body, and a Qianlong-marked bowl featuring yellow-green dragons á la the very most terrible.

The mark was superb. Nothing was missing, the lines of the mark was however too thin. Regarding fakes, I would say that they can imitate the body perfectly. The glazes are also good. For example, it is hopeless to distinguish a new yellow monochrome from an older one. It is only the manner in how the decoration is drawn that is difficult to imitate. A bad seal mark is easy to counterfeit. A premium mark is more difficult though. This I believe, however, is possible to sort out.

Modern counterfeiting of seals and marks from the late Qing are in general recognized from them being too good. The characters are sitting nervously exactly. The lines are too thin. The color is too pure and so on. It is the very definition of a perfect fake that it cannot be distinguished from the real. Therefore, it is only the almost perfect copies that can give us the clues to where the copyist's difficulty lies.

Preferred paintings by Guo Xun and Calligraphy by Shen Du.

(Before that you have Hongxi (1425) for just one year - the wind is strong at the top.)

Xuande preferred paintings by Ma Yuan and Xia Gui, the so called Ma Xia school. Significant successor in this northern academic school was Ni Duan and Li Zai. Liked to paint details from the nature. The art preferences are reflected in the porcelain decorations.

Zhe School.

Fig. 24. Flower on large platter from Hongwu (1368-98).

Directly from an exhibition in Hong Kong came a big box containing a large bowl from Hongwu (1368-98). The decoration consisted among others of flowers, with their center drawn as a cross hatched grid within a double circle. A Hongwu-fragment showed clear signs of having been shaped by vertical scratches. The glaze displayed droplets on the inside that concealed the joints well. The foot rims have clear traces of gravel mixed with ash. To explain how the objects were fired Dr. Liu drew the following two sketches to explain the differences.

Fig. 24. How porcelain was fired during the early Ming, and a foot ring from Xuande.

Some observations: The exterior shows traces of the knife used to scrape down the shape. The white glaze had the same color as usual cheap writing paper, somewhat towards gray ivory and has stains and impurities. The smashing up of failed objects occurred during this period was by one sharp blow against the inside edge. The blue color is dark blue on the gray side with oozed out black spots. The lines are unevenly drawn. On blades it sometimes happens that the stalks closer to the blade are drawn wider than near the trunk.

The color can also be a faded light gray blue. When trying to get the color darker they add more color, resulting in black bleed through. The porcelain is exactly the same gray in the fracture as on the outside. In one instance the fracture surface was colored red which probably was due to the exposure to oxygen during firing.

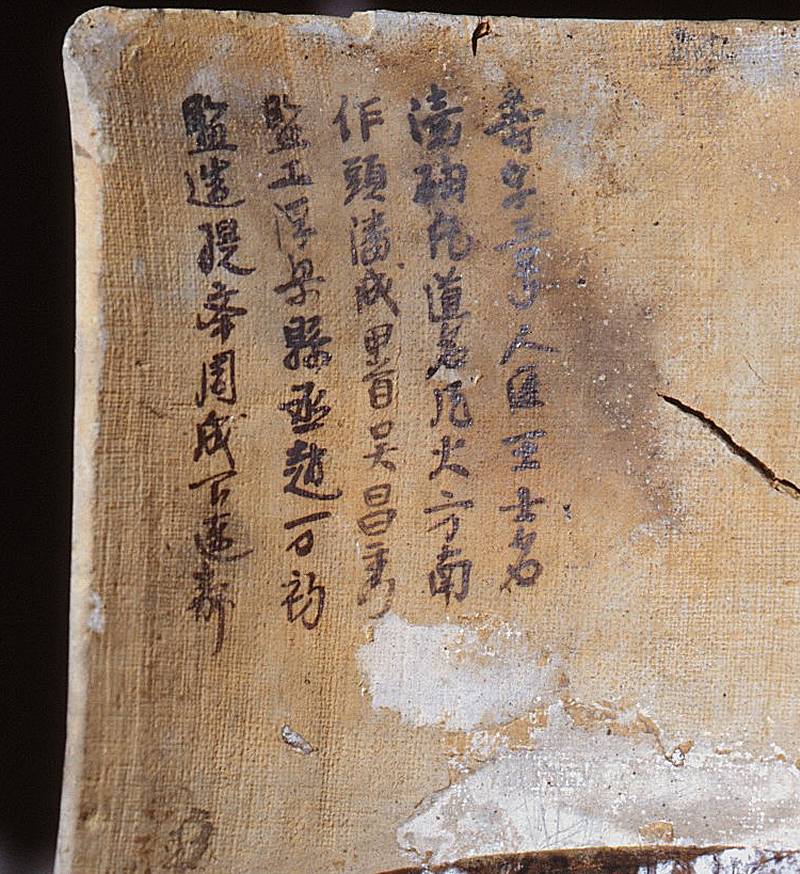

Roof tile from the 2nd year of Hongwu giving the names of a number of officials.

We were shown a roof tile where one that was superintendent at the Imperial Porcelain Factory in the 2nd year of Hongwu had written the names of a number of officials.

Fig. 24. Footrims during Hongwu (1368-98) are very different.

The most notable observation was that it during the Xuande (1426-35) probably was no special imperial kiln. Everyone needed to make porcelain and send to the emperor. Archaeologists confirmed here that "Everything in the Philippines" is minyao from Xuande (1426-35) to early Chenghua (1465-87). During Yuan (1279-1368) to Yongle (1403-25) Guanyao was sent abroad as gifts since the emperors wanted to create contact with their surrounding countries. / Footnote 2 /

In the evening, we met more privately two archaeologists in Jingdezhen. They handed over one published article each, including one on the Gaolin Mountain. We discussed the excavations they had helped to carry out and got a lot of information about things we had thought about. Some notes from our conversation:

Fig. 25. For years (centuries) waste has been dumped over the edge.