It was now time for mid-autumn festival. We invited the two archaeologists that the longest had endured our inquisitiveness for lunch, presented them with some small gifts and our interpreter, with a special Swedish-Chinese friendship pin.

During the evening we received in return three moon cakes, from the Hotel Directors, our interpreter and the archaeologists. They, the cakes, are nice but very filling.

Following A D Brankstone's map of Jingdezhen from 1937 we would seem to be living on the Pearl Hill itself, and if so, that goes to tell there has been some serious filling out here of landscapes since the early 20th century, but don't think so. We made it north up through the city, made it out to the river and then followed that all the way south until we could see the area that was formerly the old porcelain market. Red line where we walked.

This afternoon we decided to take a walk through Jingdezhen and along the Changjiang (river). I was in particular interested to take a personal look at what I had read about, the city being built on thick layers of ceramic waste and that all this could be seen at the brink and river bank of the Changjiang, floating through the city and down towards the Poyang lake and further to the Jiu jiang former customs station where the Poyang lake connects to the Yangtze and eventually to the Grand Canal, leading up to Beijing.

We first walked towards the north and eventually made it out to the river bank, and then followed the eastern riverbank south, past the floating bridge and down to the first large cement bridge, all the way down to where the old porcelain market had been where the Nanhe (South River) tributary connects from Hutian and the northeastern uplands, into the Changjiang.

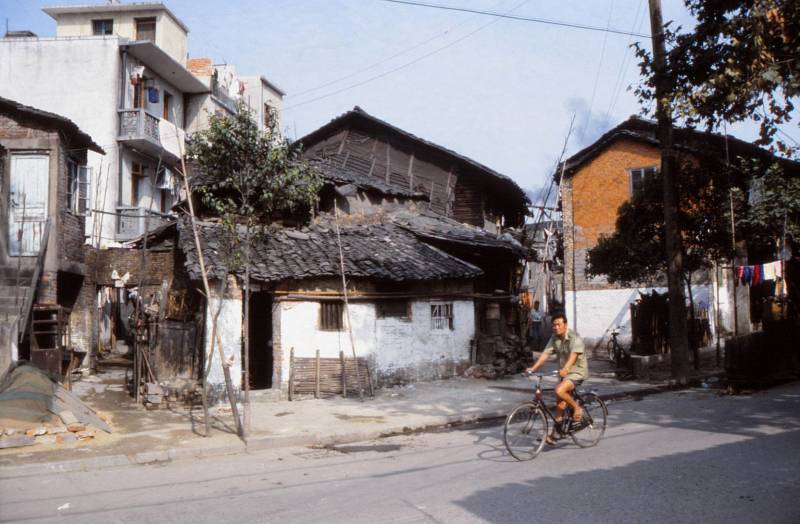

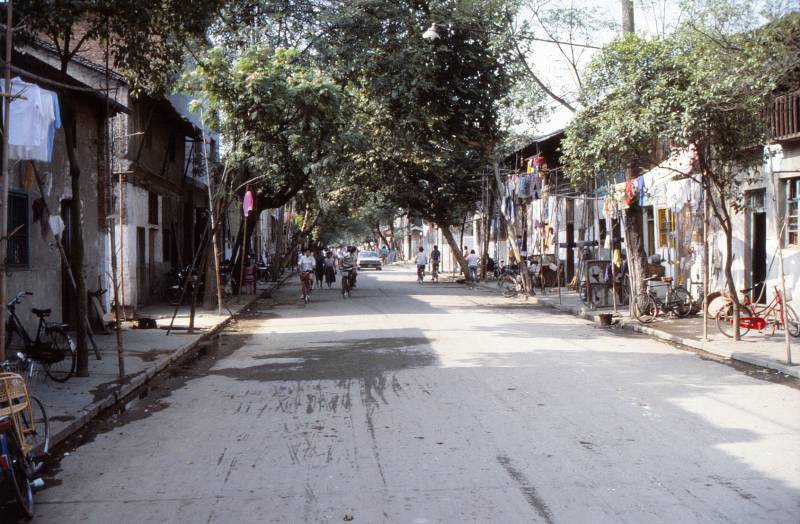

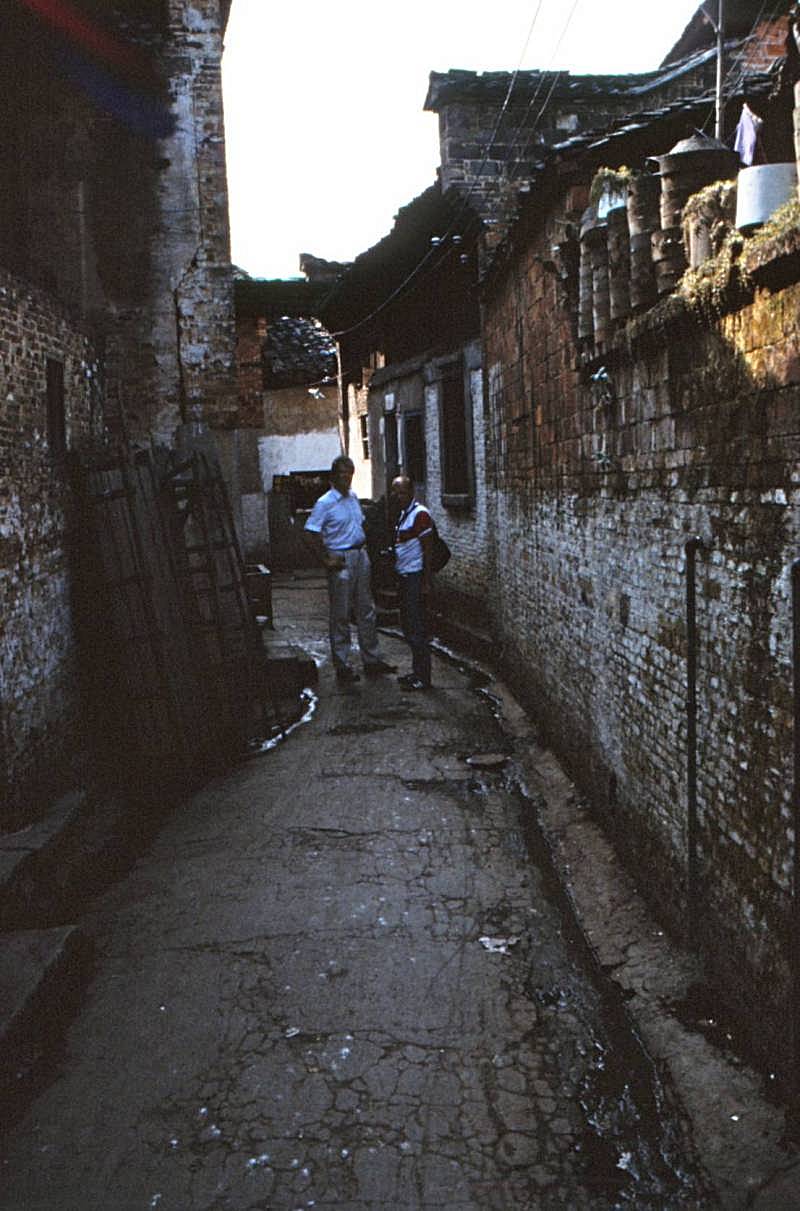

It is with mixed feelings you realize that all of this is probably going to go in the name of progress and all genuine landmarks will eventually be replaced with modern buildings.

Walked past a storage area. Looking for the history of Jingdezhen there is a photo from the 1920s that looks so much the same, it could actually be the same. It gives a perspective to think it has looked like this for hundreds of year and that it has been Wanli 'kraak' wares, Kangxi or Qianlong porcelain in those piles.

To have at most one floor of wood could be a way of dealing with fire regulations.

Walked past the Longzhu (dragon's pearl) pavilion at Zhushan. Felt comfortable to have it around just like that.

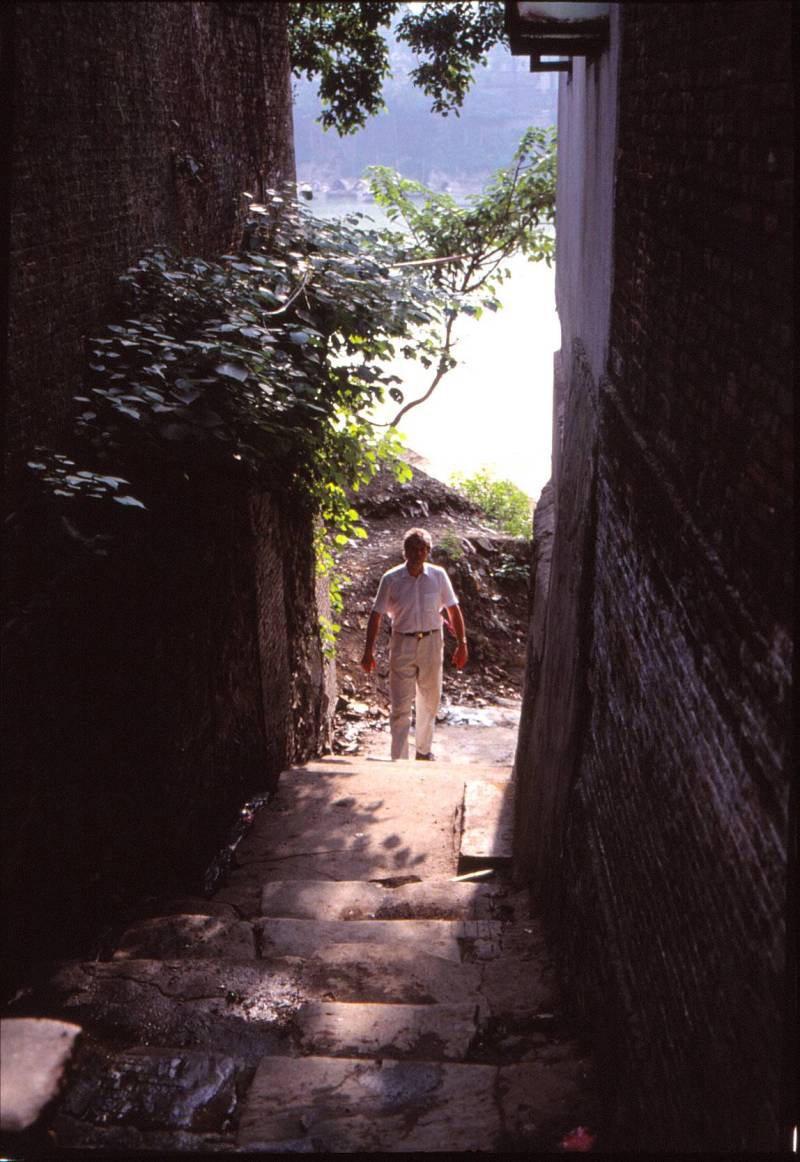

Narrow lanes are an almost certain sign of old age.

Portals over a narrow lane here can go all the way back to Ming.

Porcelain of all shapes and kinds are met with everywhere.

I forced myself to resist an urge to walk up to and check these oil jars for their age.

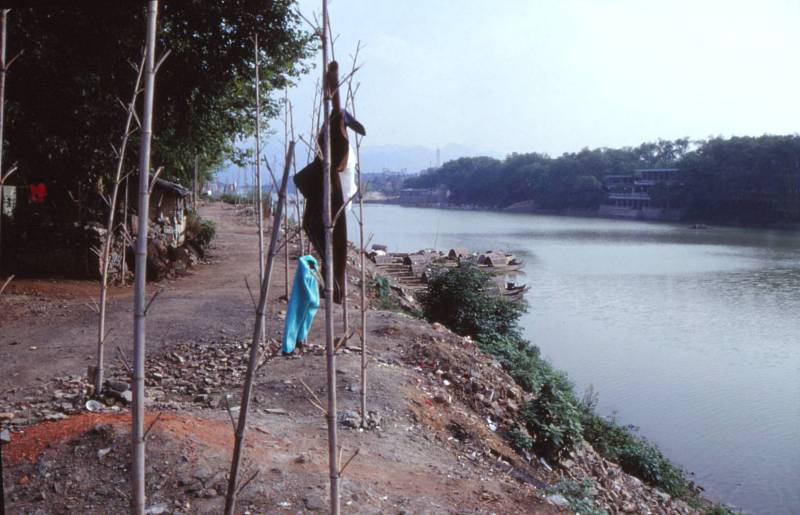

These sticks are supports for bamboo rods to hang laundry on.

They are very clever. Looking like dead trees we saw them all over the city.

We saw shards in the water, but the river mostly looked like rivers mostly do. Continuous dredging has probably together with the stream removed most of which had ended up here through time. The city's ground level was in places 8-10 meters above the river level. The river bank consisted of sand mixed soil and in some areas of construction waste. From what we saw we did not get the impression that some immense quantities of porcelain waste had been "dumped over the edge" or that "the City would rest on thick layers of porcelain". This is something we had pondered a lot.

Changjiang river looking north. Notice the the quay. Up the brink here is the city

Changjiang river looking south. The boats are of the same design as the traditional ones delivering all kinds of cargoes in and out of Jingdezhen throughout history. Down the river is the Floating Bridge that Brankstone has on his map in 1937. Immediately on the other side, over the the Floating Bridge, is the Shibadu - the Eighteenth River Crossing - precinct.

More laundry sticks. They should export these things.

The floating bridge. Shibado area to the right.

Staircase leading up and down from the Changjiang

Porcelain electric insulators used as sidewalk pavement.

Porcelain is still carried around in the city on traditional racks.

I would almost like to put it like that we almost did not see any trace of ceramic waste at all. It also appeared as if the rate of failed objects has been violently exaggerated. It occurred to me that this talk about how whole ovens often failed, may be a myth to justify better prices, and maybe to create some space in the book keeping for private ventures? When talking about that only one piece out of a thousand was good enough for the Emperor, how about reversing the numbers? What if only one in thousand was failed? Walking around here and looking at the almost superhuman skill being demonstrated in the handling of fragile objects of hardly fried clay, I would say that probably almost no objects failed completely. All the bad and semi-bad might as well have been sold, given away or buried in tombs, and are in any case they don't remain here.

Saggars are still being used as building material of houses

Looking directly at 'Nan Shan' Song Dynasty kiln area on the other side of the Nanhe. So close and yet so far away.

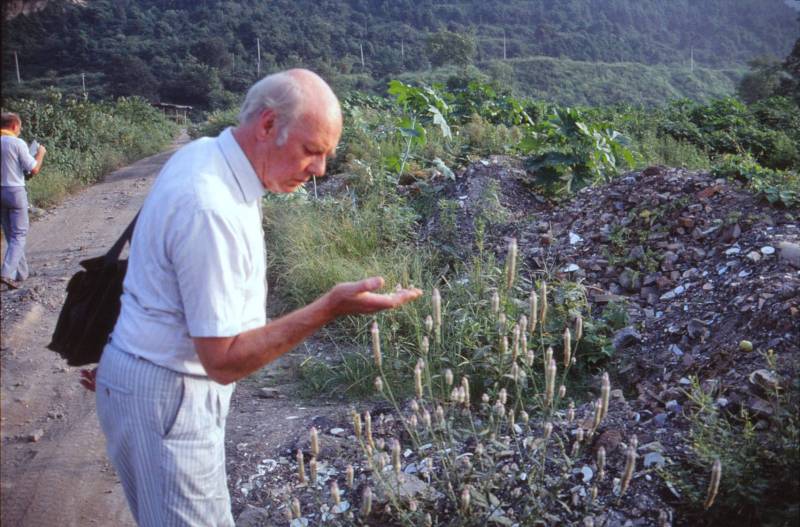

Erik Engel taking a look at what we are walking on

According to Brankstone's 1937 map, this is where the former porcelain market was, just south of Jingdzhen.

This is looking down from the road landfill eastwards in the direction of Hutian.

Nanhe from the left joining Changjiang from the right, looking downriver towards Jiujiang.

This exact route was it that all porcelain took while leaving Jingdezhen for the Imperial Court in the Beijing. Standing on the location of the old porcelain market and millions of tons of first class Kangxi porcelain shards and nobody to ask where the road fill comes from.

Also end of the road. Now, back up into the city again.

Walking back up into the city again, this area is right now being developed.

In the cargo list of the East Indiaman Gotheborg ship (1745) some of the porcelain is accounted for as having been packed

and delivered in 'bundles'. This packing method is still in use and must be hard to improve on for bowls.

At one place we saw a man actually carting away a load of broken porcelain, so it is bound to be some kind of secondary market for broken ceramics. If this has been the case also in historic times that could explain the apparent lack of ceramic waste heaps in the city.

Here they are apparently dealing in broken porcelain.

Broken porcelain recycling

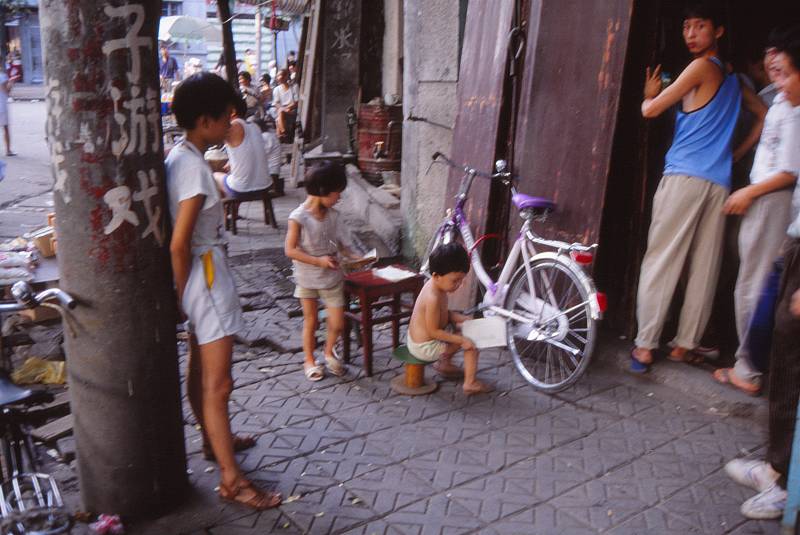

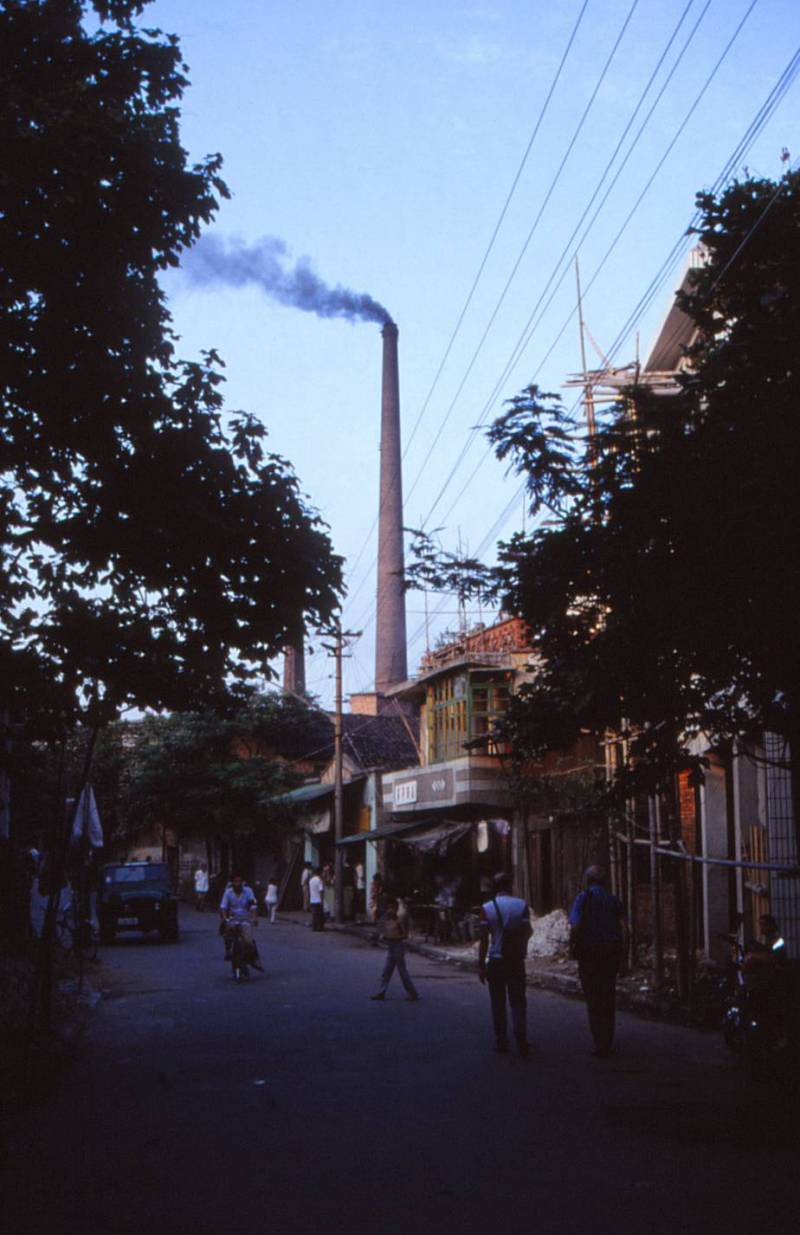

Friday afternoon and it is business as usual in a city that truly never rests.

During the walk, we only found a few shards of interest. The whole city was clean, quiet and newly swept.

One evening we were visited by some archaeologists we had not met before. They confirmed that the city was indeed set on a number of hills where valleys and depressions between the city's hills had been smoothed out over time and that the entire beach bank height in some places actually indeed consisted of ceramics.