The salvage of the East Indiaman Götheborg

–

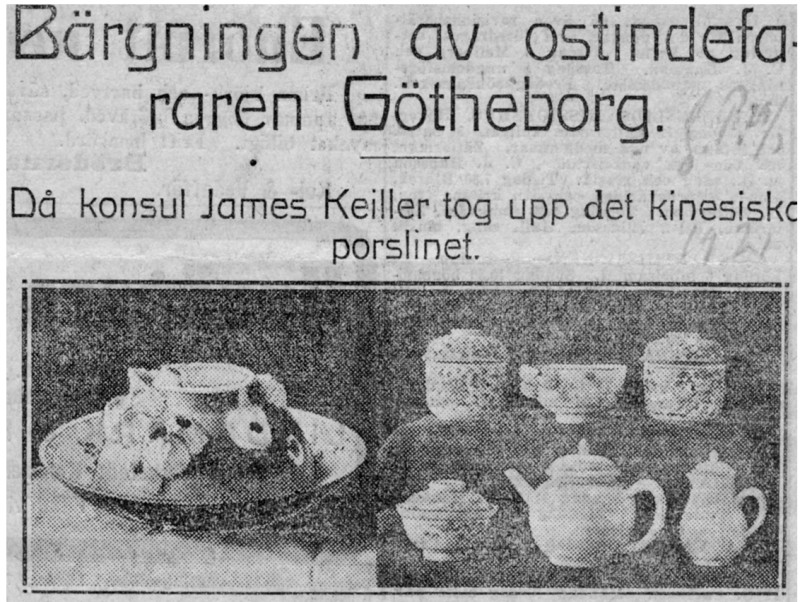

When Consul James Keiller brought up the Chinese porcelain

Newspaper clipping GP January 24, 1921

The author Eskil Olàn only briefly touches upon, in his valuable work 'Ostindiska Companiets Saga (1920)', the performed salvages of cargo from, and parts of, the great East Indiaman 'Götheborg', which, after a two and a half year expedition in 1745, was wrecked at the so-called Göteborgsgrundet, right at the entrance to its home port. The reason Olàn does not dwell more on this detail in his account is probably, besides space reasons, that the Keiller salvaging belong to more recent events.

Early Salvage Attempts

It is reported that two attempts to salvage parts of the ship Götheborg's valuable cargo were made during the latter half of the previous century. The latter of these was carried out in the 1870s and was most likely primarily intended to determine whether the claims about silver in the cargo were true. The person who carried out the salvage work appears to have blasted the ship, causing it to slide off the ground and fall apart.

It is certain that no silver was discovered, but a lot of Chinese porcelain was salvaged. However, at that time, this was not particularly valuable and probably did not reward the salvager for his efforts.

It was not until the beginning of our century, more precisely in 1905-1906, that both the cargo and the main parts of the ship were successfully salvaged. Olàn incorrectly claims that the hull still lies at the site of the accident.

James Keiller's Salvage Privilege for the Götheborg

On February 4th of that year, the then engineer, now consul, James Keiller, received the county administration's privilege for 'salvaging goods and parts from the ship Götheborg, reportedly sunk in 1745 at the so-called Hunnebådan in the Gothenburg archipelago.' The salvage was to be carried out within two years, and for this, the salvor had to observe a number of regulations regarding customs and pilotage. Moreover, the privilege letter stipulated precise regulations against shoaling the water above the shoal that was located in the middle of the shipping channel.

According to the agreement, consul Keiller, assisted by the crown pilot Hellqvist, carried out a complete measurement and mapping of the area around the shoal during the largely successful works over the following two summers, an undoubtedly very significant contribution towards the shipping.

The Salvage Operation

As a base for the salvage operations, which naturally attracted great interest from various quarters, a specially equipped barge with a cabin for the diving personnel was used. First, a detailed sketch was drawn of the ship's and the blasted hull parts' current position. It then became clear that over the years, the ship had shifted into sand and clay, away from its original stranding place on the top of the shoal. Thereafter, the divers began digging through the area.

The divers platform at anchor in the Gothenburg port entrance,

immediately above the wreck of the East Indiaman Gotheborg in 1907, "where the East Indiaman sank".

Photo from' Hwar 8 Dag (1909).

The task was to, on their knees, inch by inch, work through the partly deeply sunken ship in the mud. The workers were ordered to salvage everything that came their way, so that nothing, not even the shards from the broken porcelain, were to be missing in the expert assessment of the salvaged goods. At the same time, the find sites, i.e., the places where different parts of the porcelain cargo were encountered, were recorded. The quantity of shattered tea boxes, zinc ingots - which had probably been previously thought to be silver – rolls of silk, etc.

Thanks to the meticulousness with which the operation was conducted, a very reliable picture of the cargo's position in the old East Indiaman was obtained.

Detailed Record of Salvaged Items

As previously mentioned, Consul Keiller also had the blown-up parts of the ship brought up, namely all the somewhat preserved timber. The salvage of the colossal keel did not occur without a minor mishap. Despite the winch being quite robust, the chain broke under the great weight, and therefore another one of even larger dimensions had to be acquired. Both the keel and all the oak wood were miraculously preserved from decay by the saltwater. Large quantities of this wood, which was completely black in color and exceptionally hard, were still preserved.

If one goes through Consul Keiller's notes from the summers of 1905-06, one finds the items recorded one by one, day by day, as they were brought up. Among the salvaged items, there was a significant amount of mother-of-pearl shells, some rolls of water-damaged silk, parts of the anchor chain, various blocks belonging to the rigging, a coconut shell shaped like a punch ladle - probably used for the officers' punch bowl -, the zinc-lined but thoroughly shattered tea boxes, etc.

Recovery of the Porcelain Cargo

Through the salvage of the most important part of the cargo, the porcelain, a remarkably rich pattern collection was obtained, consisting of a vast number of service parts in various patterns, giving researchers a clear insight into Chinese porcelain manufacturing before 1745. The parts of the porcelain cargo that were protected from seawater still retain their beautiful and characteristic colors of the time[1], while those parts exposed to the dissolving effect of seawater have lost their colors completely or partially. Many porcelain pieces were fully encrusted with snails and mussels native to our waters. In our pictures, we see some items adorned in this way.

The salvaged porcelain cargo is still not in the Gothenburg Museum but is largely in the possession of Consul Keiller and his brother-in-law, Consul Carl Lyon.

Extensive Collections Acquired

The museum, a number of individuals, and others have received larger or smaller collections. The number of porcelain pieces recovered totals 4,500, of which over 3,200 were in the second year. Consul Keiller is of the opinion that there is now nothing left, or at the very least, very little, of the 'Götheborg's' cargo at the stranding site at Hunnebådan.

Curiosities in Customs and Ownership

As a curiosity, it should be mentioned that the salvagers had to pay customs duty on the recovered porcelain, despite it having lain at the bottom of the sea for no less than approximately 160 years. But that's not all; the salvagers could not consider the porcelain as their own until the customs office, formally as usual, had advertised for an owner of the salvaged porcelain for one year and one day.